How to quit lying to yourself about how long things will take

Plus spoilers for a 1999 movie you have almost certainly never heard of. Proceed with caution.

Hello and welcome to Academia Made Easier. I am so glad that you are here.

Regular readers of this newsletter know that I like to make dated or obscure pop culture references. Today I am doubling down to talk about a two-decades-old movie that received modest reviews, no award nominations, and grossed only $10 million above its costs. But its protagonist is a professor and the movie’s dramatic ending has lessons for us all, so let’s hop to it.

In Arlington Road, history professor Michael Faraday suspects his new neighbours are alt-right domestic terrorists and takes it upon himself to try to stop them. (Is there a CV category for that? Perhaps it gets listed under “service”?)

In the movie’s climax, Michael chases a van he believes is loaded with explosives into a restricted parkade. Authorities on the scene open the van. It is empty.

Michael is told, “The guy is authorized to be here. We are all authorized to be here. Everyone except you.”

The camera focuses on Michael’s face. We watch realization sink in. Michael rushes to his car. Ominous music plays. Michael opens his trunk to reveal a bomb that he himself brought into the parkade.

Boom. (The terrorist literally says “boom” as the bomb goes off. A nice touch.) The building collapses.

Cut to TV news clips about how Michael was a lone wolf terrorist. The terrorists then move into a new neighbourhood, preparing to frame a new innocent person. Roll credits.

In short: Michael’s actions created the very outcome he was trying to prevent — and then he was blamed for it.

Poor Michael.

This outcome (albeit not the terrorist-fighting lead-up) resonates with me. Far too often I find my own actions create the exact opposite of what I want. For example:

I want to connect with my colleagues — and I also tend to book too many meetings, crowding my calendar and leaving me feeling rushed when speaking with colleagues.

I want to advance my research — and I also tend to create so many new projects (shiny!) and agree to so many external invitations (flattering!) that I don’t have the mental space to advance my research.

Unlike Michael unknowingly driving a bomb into a building, nefarious others haven’t tricked me into this. The trickster, I have discovered, is me - specifically, my long-standing practice of underestimating both how long things take to complete and how much energy is required to complete things to a standard I am willing to accept.

It has taken a lot of deliberate practice to get (a bit) better about this.

If you share my tendency towards deluded optimism in estimating the time and energy involved to get things done, today’s small thing to try immediately might help you get (a bit) better about this as well.

One Small Thing to Try Immediately: Evidence-Informed Time Estimating

For this exercise, you will need something to write in. Use a notebook, Word/Docs, Excel, or whatever floats your boat. With that in hand, do the following:

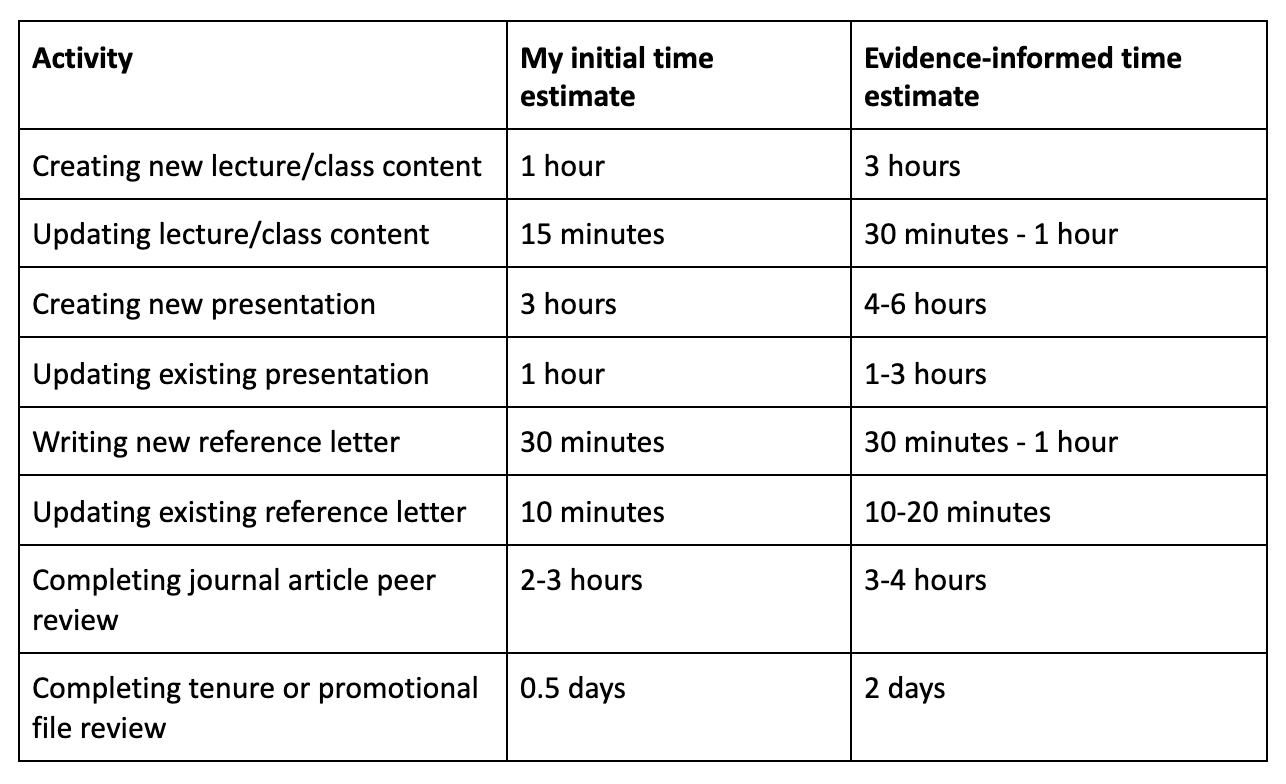

1. Create a table. Include three columns in the table: activity, initial time estimate, and evidence-informed time estimate. Include more rows than you think you need.

2. Add your key activities and initial time estimates. For activities, I suggest adding whatever comes to mind immediately; later, you can add more items as they occur to you. For larger activities (e.g., “write book”), be sure to break items down (e.g., “write chapter 1”). For the initial time estimate for each activity, write whatever your gut response is.

3. Collect evidence about how long each activity will actually take. Do the following:

If you have done the activity before, think carefully about how long it really took. If you are like me and tend to lie to yourself (“I think I only had three mini-chocolate bars”), inflate the number a bit. And then inflate it a bit more.

Ask 3-5 people at your career stage how long the activity takes them. I stress the ‘at your career stage’ point because people often get more efficient at things with experience. Early Career You might take twice as long as Mid-Career You to do the same activity. Disciplinary factors can also be relevant: I recently asked #AcademicTwitter how long it takes to peer review a journal article and the responses include a lot of variation.

The next time you do the activity, track the actual time it takes you to complete it.

Use these data to update your table. My own table is below.

Some of you may look at my estimates and think, “Wow, she is slow. I do that much more quickly.” If that is you, please share your secrets with me. Others may think, “Wow, she is fast. I do that much more slowly.” If that is you, be sure to sign up for Academia Made Easier (it is free!) for future time-saving ideas.

4. Use the evidence to inform your decision-making. Evidence in hand, do one or more of the following:

Evaluate if you truly have the time needed to take on the activity.

Allocate the appropriate amount of time in your calendar for the activity.

Renegotiate deadlines when needed.

Determine if you need to ask for help to complete an activity. For example, you might ask a student requesting a reference letter to write a draft that you can rewrite in your own words, or have them compile a clear list of relevant information (classes, dates, grades) to inform your letter.

Assess if you can automate part of the activity. For example, you might create a template structure that you use for all reference letters.

Decide if you are willing to lower your standards on some aspect of the activity to reduce the time needed.

To what extent do you already use evidence to inform your own time estimates? Please comment to let me know!

Chipping Away: What I Have Been Up To

A quick update on some of my own activities since my last newsletter, since I have your attention:

I co-led a workshop on Work Your Career: Get What You Want from Your Social Sciences or Humanities PhD at the Canadian Career Symposium for Graduate Students and Postdoctoral Fellows. If you are a PhD student of any discipline or if you work with PhD students in any capacity, Work Your Career has information useful to you. Check your public or university library, and if it is not there, consider asking them to add it to their collection. Or - just putting this idea out there - consider getting your own copy.

Most recent TV binge-watch: Squid Game. Yowsa. I am happy to report that I drew no parallels to my own life from that one.

Autumn running this year has been amazing. While I usually run alone, occasionally I take my neighbour dog Hank along. The runs are much slower, with more sniffing, stick inspecting, and breaks to discuss leash etiquette than when I run alone, but he is pretty irresistible.

Until next time…

If my counting is correct, my next Academia Made Easier newsletter will be number 20. Twenty! That is a lot of small ideas. Perhaps when I get to 50 I share a big idea for a change. Time will tell.

Stay well, my colleagues.

P.S. If you read the small idea above and thought “this is too much work”, here is an even easier trick: just take whatever your initial estimate is and triple it. Future You will thank Past You. Trust me.

Loleen Berdahl, Ph.D.: I am a twin mother, wife, runner, cat lover, and chocolate enthusiast. I spend far too much time on Twitter and binge-watching television, and my house could be a lot cleaner. During the work hours, I am the Executive Director of the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. I am the author of University Affair’s Skills Agenda column and my most recent books are Work Your Career: Get What You Want from Your Social Sciences or Humanities PhD and Explorations: Conducting Empirical Research in Canadian Political Science.

I LOVED Arlington Road. I never thought it got enough attention.

I appreciate this post! And I have a suggestion for acquiring evidence of the time required for various activities, although it takes a while to accumulate that evidence. A few years ago, I bought an inexpensive time tracker app (I use Tyme2). I was curious to know how much time I was spending on certain kinds of activities and how many hours per week I was actually working. It was easy to set up and it's in my menu bar for easy access. I simply click to start the timer whenever I begin a new activity; each activity has its own category/label so that I can differentiate the time spent on each one. The app notices 15 minutes of inactivity and asks if I meant to stop the timer or not so I don't have to worry about walking away from the computer without ending a task. It's now habit for me to use the timer and I now have three years of evidence of the time I've spent on various activities. After a hard week, it's very satisfying to look back on all that I did. When I feel guilty about taking a day off, I simply look at all the hours I've put in over the weeks -- including on weekends -- and then I don't feel so guilty. And when I'm asked to take on a new task, I have hard evidence of the time it has taken me to do similar tasks in the past. Tracking time like this obviously requires some consistency and commitment but it works for my A-type OCD personality (which I think I may share with many colleagues -- just a hunch). It is super quick and easy once it becomes a habit!